Korean Copyright Reform: Don’t Stifle Korean Filmmaking

The Korean film industry is one of the major artistic and cultural successes in Asia. The industry was propelled to prominence in Europe and North America through the 2019 film “Parasite”, which won the Palme d’Or at Cannes and Best Picture (plus three other awards) at the 2019 Academy Awards. Korean films have come a long way from the days of the “screen quota”, a measure first imposed by the Korean government back in the 1960s in an effort to promote Korean content. It required Korean movie theatres to devote a minimum of 146 days per year to screening Korean films, and became a major bone of contention between Korea and the US in the period leading up to the negotiation of the Korea-US free trade agreement. The screen quota had the perverse effect of forcing many theatres to go dark for weeks at a time for want of Korean content. A much-reduced screen quota still exists on the books but has become moot because of the spurt in creativity of Korean filmmakers and the resultant investment in the sector. This demonstrates that good stories, production values and talent make films commercially viable, not government quotas. Typically, domestic Korean films take 50-60 % of the box office, a high percentage in comparison to many other countries. The Korean film and television industry generated a total economic contribution of USD18.45 billion in 2018 and supported over 300,000 jobs. That is quite a record—but it is in jeopardy.

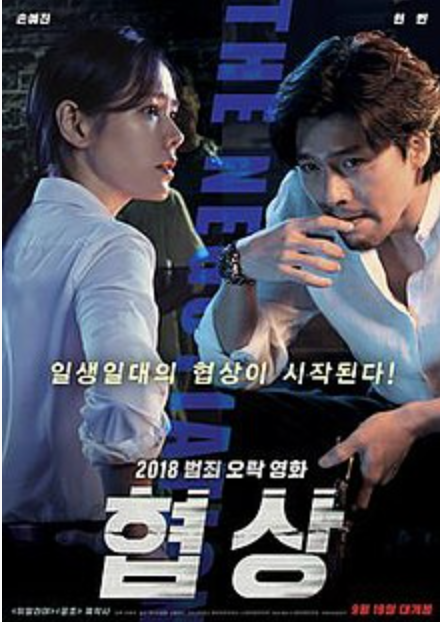

Korean filmmakers, like those in other countries, draw inspiration for telling compelling stories from real-life events, but a currently proposed amendment to the Korean copyright act could put such historically or “true story” based films at risk. The amendment would create a “portrait right”, which would be accorded to “a person (in Korea) who can be widely recognized by the general public as the object of a portrait”. This would confer a property right on that person or their estate that could be utilized commercially. The right would exist for the lifetime of the person in question plus an additional thirty years. It is unprecedented for portrait or publicity rights to be incorporated into copyright law, and its enactment could enable publicly recognizable persons to block film productions in which they are portrayed. Recent domestic box office and artistic successes such as “The Age of Shadows” (a 2017 Academy Award submission) or “The Man Standing Next” (selected for the 2021 Academy Awards for Best International Film) might not have been made.

The great stories told through movies and television productions that we all enjoy so much are inspired from a variety of sources—novels, sci-fi epics, history, traditional children’s tales and, of course, real-life events and people. In a non-Korean context, think of films like Flight 93, Saving Private Ryan, Argo, All The President’s Men and others that are based on real-life events (although considerable poetic licence is usually incorporated into the scripts). Then there are biodramas like Milk, The Iron Lady, Erin Brockovich, and The King’s Speech, not to mention the popular Netflix series The Crown, with Season Four now released. Some of these works hew more or less to the historical record, others use real characters in highly fictionalized roles. There are also documentaries that tell a story using actual footage, some well-known recent ones being, They Shall Not Grow Old, Social Dilemma, Tiger King, Wild Wild Country, and so on. We all have our favourites. You can add your own. Now imagine that someone featured in those films objects to the portrayal of themselves, or perhaps a family member of a portrayed deceased person objects, can you imagine the chilling effect on creativity?

Find original piece here.