Muhammad Feroz Al Mamun (foreground) and fellow villagers working in the jute and tobacco fields in Bangladesh from I Dream Of Singapore. Photo: Looi Wan Ping

According to a February 2020 survey by lpsos, a global market research firm, nearly four in five of 913 Singaporean respondents aged 18 to 64 agreed that the nation’s economy is rigged to give the rich and powerful an advantage.

For the migrant workers steadily streaming into Singapore with their own idea of the Singapore dream, the predicament is as unpalatable as it is for locals, and even more difficult to stomach.

Ethan Guo, general manager of TWC2, says it is almost impossible for migrant workers to get fair treatment, which creates the perception that the rich and well-connected always get their way while the poorer or the less socially mobile never do.

“In general, living in Singapore is hard because there’s very little room for sympathy, or [any] sympathy … built into the system,” says Guo.

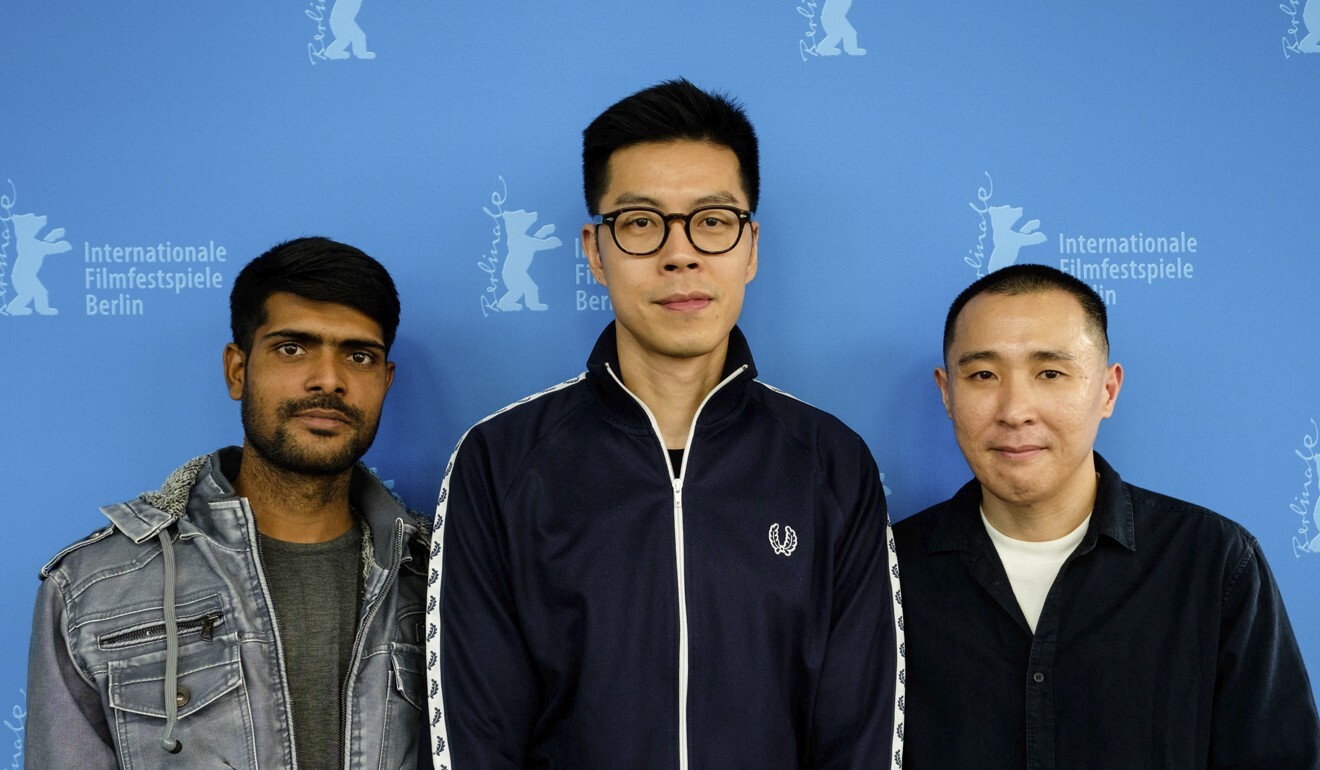

A Land Imagined director-writer Yeo Siew Hua wins the Golden Leopard Award. Photo: Locarno Festival

Through filmmaker Lei’s lens, the audience is given an insight into the bureaucratic barricades that migrant workers have to overcome, as well as the loneliness and homesickness that permeates their daily lives. “Waiting at the shelter is really just what they do,” says the director. “Because of language and cultural barriers, they don’t have many Singaporean friends except fellow Bangladeshi roommates.”

This alienation is also apparent in Yeo’s A Land Imagined, which won the Golden Leopard Award at the 71st Locarno Festival in Switzerland, where the stark despair of the “insignificant” foreign worker is evident throughout.

“There haven’t been many films made about the migrant experience in Singapore, which I find very strange since a quarter of the demographic living in Singapore is migrant,” the director says. “The few stories that are told about them focus on their work and function in society.

“I had hoped to focus on their lives outside these convenient categories of impoverished foreign labourers, try to show the humanity we share in common, and also their dreams.”

Serangoon Road in Little India, Singapore in a still from I Dream Of Singapore. Photo: Tiger Tiger Pictures

In contrast to the migrant worker in A Land Imagined trying to find his way out of a desolate and godforsaken Singapore landscape, Lei’s I Dream of Singapore captures the country’s Marina Bay Sands and Gardens by the Bay looming in the background as emblems of the aspirations that took root in Feroz’s mind.

In the end, Singapore did not fit the picture he envisioned. Now back in Bangladesh, helping his ailing father with farm work, Feroz says he is happy to have had the chance to live in Singapore.

“I like that Singapore is neat, clean and has good food,” he says. “But when I was working there it was difficult. My boss always pushed us to be faster; we couldn’t even rest for three minutes.”

A still from I Dream of Singapore by Lei Yuan Bin. Photo: I Dream of Singapore

Lei uses Feroz’s viewpoint as a migrant to push his audience to see Singapore in a new light. He also seeks to explore universal issues such as social inequality in a Singaporean context.

Currently working as editor and cinematographer on a new documentary about transgender phobia in the state, Lei will be looking at the subject with a sympathetic eye. “I’ll be working with a Singaporean transgender director,” he says.

Yeo is also trying to tell stories that he cares about; some of them, he says, will “inevitably deal with the social contexts I inhabit”.

“There haven’t been many films made about the migrant experience in Singapore, which I find very strange since a quarter of the demographic living in Singapore is migrant. The few stories that are told about them focus on their work and function in society”

Yeo is developing a feature film that looks at how people’s existence is tied to image-making, and set against the backdrop of a high-surveillance city state.

“I think the reality is that we are all trying to realise our own separate versions of our imagined lands and, naturally, those who are more privileged get to realise it more,” says Yeo. “But I’m curious: does a place like Singapore have the will and capacity to include the diverse imaginations it has within itself? What would this collective imagination look like? I’m excited to know.”

This article was first published here.